Archbishops Boulos Yazigi and Youhanna Ibrahim. (Credit: Jaimee Haddad)

"It's not the regime," former head of General Security Abbas Ibrahim refuted. "I fail to see the interest the Syrian regime would have had in kidnapping archbishops. It's nonsensical," added Director of L'Œuvre d'Orient Pascal Gollnisch.

It has been eleven years since the abduction of the two archbishops of Aleppo shook the Eastern Churches. Every April since then, they revive their memory and pray for their brothers, but cannot answer the questions. Who is behind this act? Are the archbishops still alive or have they been murdered? Officially, no one knows.

The abduction was never claimed, and no ransom was demanded. There was no evidence and few leads. It was as if they had vanished into thin air. The nagging question remains: Why were they targeted?

To try to answer this question, it is essential to understand the context of that time. The Syrian war had begun two years earlier. The opposition was gaining ground but was divided and infiltrated by Islamist groups. Their presence instilled fear, especially among the Alawite and Christian minorities whose support was essential for the regime's survival. The regime did not hesitate to fuel this fear and consolidate its power. It presented itself as the last bastion against fundamentalists, the protector of some against others. This rhetoric appealed to the minorities in the region and certain segments of Western public opinion. The local religious authorities had to be the best advocates of this rhetoric.

Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim during a meeting with Austrian politician Reinhold Lopatka, 2012. (Credit: Under Creative Commons license)

Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim during a meeting with Austrian politician Reinhold Lopatka, 2012. (Credit: Under Creative Commons license)

Head of the Greek Orthodox Church and Patriarch of Antioch and the East Youhanna Yazigi indicated that he did not share this view in his first press conference after his appointment on Saturday, Dec. 22, 2012. "What is happening to us is happening to others as well. We are in the same situation as anyone else, Muslims and Christians, standing alongside each other facing difficulties," he said. This would be his only statement outside the norm. Four months later, his brother, Archbishop Boulos Yazigi, disappeared with Ibrahim. Was he directly targeted through this abduction? Nothing in our investigation allowed us to assert that. Especially since his brother was a discreet man who happened to be in the convoy stopped that day by chance.

"He considered the Christian world in exile a reality and not a fate."

The further our investigation went, the more this became evident. Youhanna Ibrahim – Mar Gregorios and the second archbishop – was the central figure in this story. "He was the most important target," emphasized the president of the Syrian National Council, Georges Sabra.

Youhanna Ibrahim was born in 1949 in Qamishli to a family of survivors of the 1915 Armenian genocide. He became a monk at the age of 25. This marked the beginning of a meteoric rise. He flew to Rome, to the Pontifical Oriental Institute, in the early 1970s. At the age of 30, he was already appointed Archbishop of Aleppo. He pursued further studies in England and the United States. "He was extremely cultured, very intelligent and charismatic, quickly becoming a high-ranking religious figure," recounted one of his friends, Syrian political scientist Salam Kawakibi.

"He understood that his Church was in transition. That the time of the all-powerful village priest was over. Even before the invasion of Iraq or the massacres of Nineveh or Mosul, he sensed that Christians were going to open up internationally," said the French writer and journalist, specialist in religious minorities, Sébastien de Courtois, who knew him. "He was one of the first archbishops to tour Europe to meet the communities. He considered the Christian world in exile a reality and not a fate," he added.

Razor's Edge

While some prelates turned their backs on Christian dissidents, Youhanna Ibrahim worked to keep them out of prison. After his release, Fouad Éliaa – his friend and survivor of the abduction, who was imprisoned for a year in 1980 under Hafez al-Assad – met him for the first time. "'Hamdellah aas-salame. We are proud of you'," he told him. "He worried about us, but he was not in favor of fighting against the regime. He was pragmatic," said writer and researcher Sleiman Youssef, also from Qamishli.

This was a tightrope that became untenable after the outbreak of the revolution in March 2011. The violent repression of the regime against peaceful protesters took its toll on his pragmatism. In the first weeks, he understood that this chapter would be different from the others. "With the assassination of thousands of civilians, something awakened in him. He believed he was ready to intervene, to speak to everyone. But he was a man of the Church, not a political activist like Paolo (Dall'oglio)," explained Salam Kawakibi, referring to the Italian Jesuit priest and opponent of the Assad regime kidnapped by the Islamic State in Raqqa in July 2013.

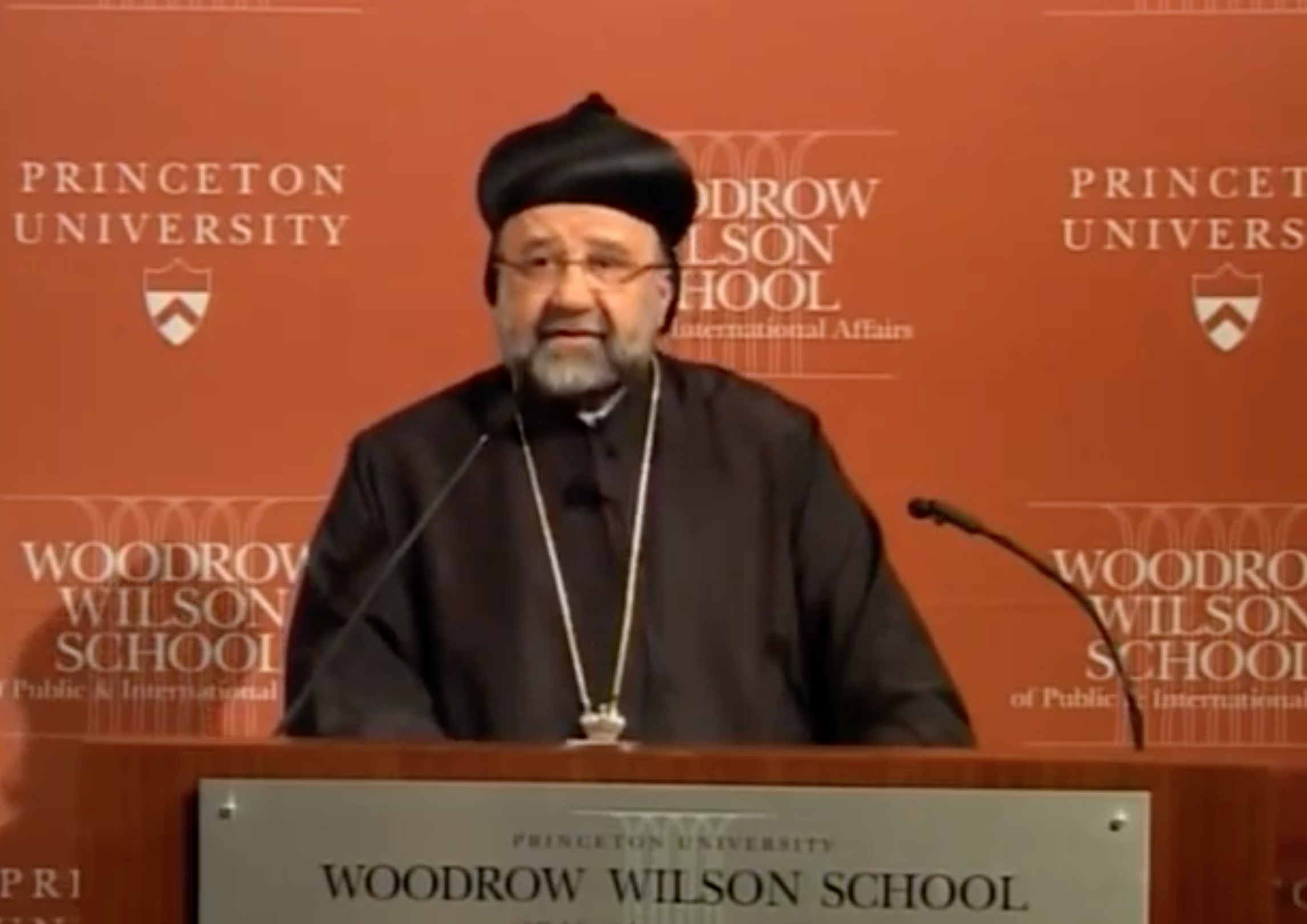

On Oct. 24, 2012, Mar Gregorios was invited to speak at Princeton University in the US. The conference was filmed. He did not mince his words. At the podium, he warned from the outset that he was "not a politician but an archbishop ... I am here on behalf of religious people."

Yet he then meticulously deciphered the Syrian situation, proposing a real roadmap out of the crisis. "We must elect a new president, a leader capable of maintaining the situation in Syria and returning it to a safe, stable and democratic state," he said. In the audience, a professor asked him about the relationship between the clergy and the government. "Before March 2011, we praised the regime, the president. It was tradition ... [myself] included. But after, we couldn't imagine that in Syria, the bloodshed would change everything in people's lives," he replied.

Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim invited to speak at Princeton University, Oct. 24, 2012. (Credit: Screenshot of the filmed conference)

Archbishop Youhanna Ibrahim invited to speak at Princeton University, Oct. 24, 2012. (Credit: Screenshot of the filmed conference)

He was "invited" to speak in front of a very different audience two weeks later. The speech was less confrontational. On Nov. 18 and 19, 2012 (five months before the abduction), the Syrian National Dialogue Conference was held in the hall of a grand hotel in Tehran by the Iranian Foreign Minister at the time. The name of the meeting? "No to violence... Yes to democracy and popular will." At the time, the Iranian regime – an ally of Damascus – was trying the diplomatic card. For the first time since the beginning of the conflict, it managed to bring together members of the opposition and representatives of the government.

Once again, the archbishop traded his homilies for a genuine political plea. "All Syrians – after this popular movement that has lasted for a year and eight months – hope to increase public freedoms even further," he said. "Allow me to be frank with you. Before denouncing the plans of the West, which threaten civil war, we must purify our visions." He then urged all parties to the conflict to work together towards a ceasefire and proposed several initiatives once again to stem the crisis. This speech from a member of the Syrian clergy in Iran was not insignificant. "Even before the war, he was advocating dialogue between all components of Syrian society and between political forces, those close to the regime as well as those of the opposition," related Sleiman Youssef.

He found his way to Damascus...

Archbishop Ibrahim believed he was protected because he knew he was respected and had support within the nomenklatura. "Since the beginning of the revolution, he has always refused to speak in Syrian media," said Éliaa. In foreign media, however, he spoke more regularly, but he was careful not to cross the line.

"Despite this, he received several warnings," recalled a close associate on condition of anonymity. It only took a sentence, a word, to be condemned. The increasing violence of the fighting pushed thousands of Christian families to flee to Lebanon or Europe. By April 2013, a third of this community of one and a half million souls had already left. Those who had no choice but to stay were tolerated on the condition that they submit to the regime. Almost all of their religious leaders interviewed by the Western press echoed the government's propaganda. "We were portrayed as radical Christian slaughterers. It scared them," said Abderrahmane Allaf, the lawyer and dissident who accompanied the prelates in rebel-held areas. Ibrahim, however, adopted a new posture that he defended with conviction. He found his way to Damascus.

'I warned him that he had gone too far'

On April 13, 2013, he dropped several 'bombs' in an interview with the BBC in Arabic. That day, a woman and her two sons were suffocated by sarin gas launched by the Syrian army. It was probably a first in Aleppo. The red line was crossed. But Mar Youhanna did not know it yet.

Nevertheless, he unleashed his thoughts in this interview of a few minutes with the British channel. In the face of the Damascus discourse, he affirmed that there was "no plan to kill Christians," that they "were not targeted, nor were the churches, but they suffered indiscriminate attacks."

The survival of Syrian Christians is not linked to the survival of President Bashar al-Assad's regime.

"I hold everyone responsible for these killings, this corruption. I do not only blame the opposition or the regime," he said, accusing the latter of not managing the crisis better. The prelate also expressed doubt about the official figures of the dead and wounded. He called on the government to "open its doors to the media so that they convey the true image of the tragedy suffered by the Syrians." But this sentence must have tipped the scales: "The situation in Syria is different from that in Iraq ... the survival of Syrian Christians is not linked to the survival of President Bashar al-Assad's regime."

In his entourage, these statements caused terror, while pro-Assad trolls reveled on social media. "We were terrified of possible repercussions. We couldn't understand how he could say that. Some advised him to go into hiding until things calmed down," recounted his nephew Jamil Diarbakerli, executive director of the Assyrian Observer for Human Rights, an NGO based in Sweden. "I warned him that he had gone too far. He replied, 'It's too late,'" confided a Syrian friend from the opposition, speaking under anonymity.

It took nine days for the axe to fall. When news of his abduction with Archbishop Yazigi spread, several close associates interviewed by L'Orient Today immediately "realized that he was no longer alive." "I even expected it to happen sooner," lamented Ayman Abdelnour, president of the opposition NGO Syrian Christians for Peace.

A banner calling for the release of the two archbishops, in front of the Saint-Marc monastery, in Jerusalem in 2013. (Credit: Wikicommons)

A banner calling for the release of the two archbishops, in front of the Saint-Marc monastery, in Jerusalem in 2013. (Credit: Wikicommons)

"My uncle was going to become the next Syriac Orthodox Patriarch. The regime was probably not reassured to see someone like him reach such a position because he did not bow down," suggested Jamil Diarbakerli, who never believed in the Islamist track.

In such a silenced country, where the mukhabarat (intelligence service) infiltrate all strata of society even within the opposition, the state nevertheless failed to solve this case. But did it even want to?

After a sham investigation, there has been radio silence. After the abduction, Fouad Éliaa spent over a week searching the outskirts, on the opposition side. "I was called asking what I was doing. I told them I wasn't afraid to return to Aleppo, but that I wanted to continue the search a little longer," he said. Upon his return, about 15 days later, he was questioned by the air force intelligence. "I had a ... two-minute interrogation. They accused me of being an accomplice of the kidnappers and then let me go," he recalled.

Meanwhile, Archbishop Ibrahim's apartment and office at the archdiocese and St. Ephrem Cathedral, were ransacked. "They searched everything looking for 'evidence' that could have compromised the true sponsors of his disappearance," recounted his nephew.

In Aleppo, Qamishli and elsewhere, this abduction marked a turning point for Christians. "It pushed many of us to consider emigrating," lamented writer Sleiman Youssef. "An important Levantine cleric told me during his visit to Sweden that he refused to discuss the subject to avoid facing the same fate," said Jamil Diarbakerli. "He's not the only one who told me that." At the Sofitel on April 17, during the commemoration of their 11 years of disappearance, organized by the Orthodox Encounter and the Syriac League, the speakers — bishops and political figures — did not mention the Syrian government once, but blamed the "Westerners who did nothing to shed light on the matter."

"Over the years, I have observed that everything has been done to stifle the matter and try to close the chapter. I am surprised that none of the ecclesiastical authorities dared to call for the opening of an international investigation, " he deplored. No official representative of the Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox Churches wished to speak as part of this investigation.

The former (late) patriarch of the Syriac-Orthodox Ignatius Zakka I Iwas of Antioch, Mar Gregorios Ibrahim and Georges Saliba, current Syriac-Orthodox bishop of Mount Lebanon and Tripoli, October 2010. (Credit: Screenshot from an interview with Jason Hamacher, an American musician in Aleppo)

The former (late) patriarch of the Syriac-Orthodox Ignatius Zakka I Iwas of Antioch, Mar Gregorios Ibrahim and Georges Saliba, current Syriac-Orthodox bishop of Mount Lebanon and Tripoli, October 2010. (Credit: Screenshot from an interview with Jason Hamacher, an American musician in Aleppo)

The representatives of the Syrian clergy are still convinced that they made the rational choice by supporting Bashar al-Assad rather than siding with the oppressed. Whether they are Christians, Druze, or Muslims, the Assads eliminated all forms of political opposition, in Syria and Lebanon, for several decades. A section of the mukhabarat is even dedicated to controlling religious institutions. '"It is them who meddle in the elections of religious figures to key positions, and who go so far as to write the Sunday sermon of the patriarch or the sermons of the mufti," explained Georges Sabra.

'Turning the page'?

After years of hoping for their return, the Churches made the painful decision to replace their archbishops. The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate was the first to do so in October 2021 by appointing Ephrem Maalouli in Boulos Yazigi's place. In September 2022, the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate appointed Boutros Kassis as the successor to Youhanna Ibrahim. "These decisions were seen as turning the page. But this matter does not die. It has become a symbol," said Marwan Abou Fadel, Secretary General of the Orthodox Encounter.

No one seems to believe they could still be alive. But no one dares to make it official either. "I think they are dead. We have had some information that they have been killed," confessed Abbas Ibrahim. What information? The former head of the SG no longer responded. Then he continued, "By whom? How? No one knows."

"They are no longer of this world."

A few months after launching a petition in 2017 calling on the US to help free the two archbishops, Joseph Hakim, president of the International Christian Union, claims to have received a message from a source close to the US administration. "They tell me that they were killed 'a long time ago' and that it was useless to waste our time," he told L'Orient Today.

This conversation would conclude the searches of another envoy sent by the Eastern Churches. In 2018, as he got a little too close to a lead, a Syrian friend came to deliver a message to him. The envoy recounted this conversation years later to L'Orient Today on condition of anonymity.

At that time, Syria was still in turmoil. Some 350,000 people had died, and tens of thousands had disappeared. Six million lived in exile and almost as many were displaced. Resurrected by its Russian godfather and Iranian ally, Damascus managed to reconquer Ghouta and then Deraa, the cradle of the revolution and its tomb. The regime had regained strength. It felt out of the woods.

One evening, two prominent figures feasted in an upscale restaurant in the Syrian capital. They drank a little too much. One of them confided, "Go tell the Lebanese to stop their searches. They are no longer of this world," said this Baathist bigwig to his stunned interlocutor. "Youhanna Ibrahim had too loose a tongue..." he finally admitted.